Egypt’s Three Revolutions: The Force of History behind the Uprising

When the Egyptian Uprising of 2011 began, we heard media pundits, friends, and colleagues milling about in search of apt metaphors to describe the mass protests and revolution in Egypt. In so far as “history” was mobilized in these discussions, it was generally as repetition or analogy. Hence: the Berlin Wall; Tiananmen Square; the first Palestinian Intifada; the Iranian Revolution; the Paris Commune; and the French Revolution, as well as Egypt’s own 1919 and 1952 revolutions. But do these vivid comparisons conceal more than they reveal? Indeed, one could argue that one of the most striking aspects of the contemporary media discussions surrounding Mubarak’s Egypt is the absence of any real sense of history. It is not enough to fill this void with rhetorical comparisons and poetic license.

While an understanding of the process of privatization, economic marginalization, consumerism, and structural adjustment that we refer to as “neo-liberalism” is crucial to understanding the contemporary unfolding of events, particularly in terms of the existence of vast economic inequalities and the impoverishment of the demographic masses, a focus on neo-liberalism alone fails to address the question of the historical relationship in Egypt between ruler and ruled. What would a longer-term historical perspective, a deeper structural view of the events in Egypt look like? Focusing on popular protest and mobilization in Egypt’s 1919, 1952, and 2011 revolutions, I focus on the internal dynamics of, and discontinuities between, each of these revolutions, characterizing them as nationalist, passive, and popular, respectively.

A primer in Egyptian history

1919 revolution

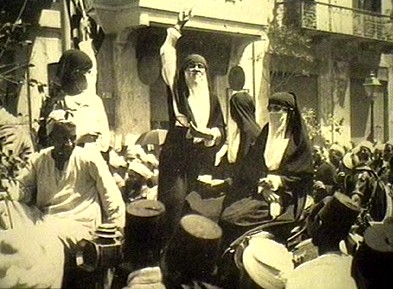

Egypt, occupied by Great Britain in effect since 1882, achieved its independence from colonial rule only in the aftermath of sustained protests. In the wake of the 1919 revolution, and after two years of stalled negotiations, the British abolished martial law and granted Egypt unilateral nominal independence from colonial rule in February of 1922. Despite this, the British continued to maintain control over the security of imperial communications, the defense of Egypt, the protection of foreign interests and minorities, and the Sudan. The 1919 revolution had two stages: the violent and short period of March 1919 that involved large-scale mobilizations by the peasantry in rural areas that were suppressed by British military action; and the protracted phase beginning in April 1919 that was less violent and more urban, with the large-scale participation of students, workers, lawyers, and other professionals.

The economic and political crises of World War I, experienced in Egypt as the expansion of the colonial-state bureaucracy, the forced conscription of Egyptians, the state appropriation of cotton production, and the forcible provision of supplies for British troops resulted in a crisis of political control. In the competition for political power that ensued between the effendiyya (middle class nationalists) and the colonial regime, the Wafd or delegation Party (Egypt’s major nationalist political party throughout much of the first half of the twentieth century) and the 1919 rebellion were born. But was 1919 a unified uprising in which peasants, workers, and politicians coalesced in support of a nascent nationalism when the British failed to give Egypt its promised independence?

In the urban context, 1919 represented the consolidation of a labor movement (trade unions, labor activism, nationwide strikes) that was forged at the intersection of national and class-consciousness.1 Such labor movements were enveloped within the anti-colonial nationalism of the time, while more radical leftist groups were unable to gain a foothold in the context of the Wafd’s moderate nationalist platform of removing foreign economic and political exploitation. Further, the mobilization of the peasantry and momentary subversions of the rural order did not in fact materialize into a wide-scale peasant revolution; the Wafd (striving for political sovereignty and parliamentary democracy) continued to oscillate throughout its tenure between populism and social conservatism. Some have argued that the nationalist call for “independence, freedom, and justice” could not have held the same meaning for peasants, who sought to liberate themselves from the colonization of their economic life by landowning interests, as it might have had for the urban intelligentsia.2 Whatever perspective we adopt, it is clear that the 1919 revolution meant different things to different segments of the population. But, at least from the perspective of the emergent dominant national ruling elements, it did not aim at the radical transformation of the social structure or class relations, but rather at the assertion of territorial nationalism in the face of British colonialism. In other words, it was a nationalist revolution.

1952 revolution

Prior to 1952, the Palace, the Wafd and a multitude of oppositional groups ranging from Communists to Muslim Brothers characterized Egypt’s political landscape. This intensely variegated ideological landscape was marked by a commitment to economic nationalism and a desire to rid Egypt completely of foreign control, in particular the presence of British troops on Egyptian soil. Further, the larger question of complete political independence was cross-hatched with the economic difficulties faced by the majority of the population. The years after 1929 were the years of the worldwide economic depression, and during this time agricultural wages fell an estimated forty percent. The 1930s were characterized by wide scale unrest with the increased activity of peasants, workers, and trade unions, student agitation, and demonstrations.

Egypt’s 1952 military coup and revolution led by Gamal Abdel-Nasser and the Free Officers ousted Egypt’s decadent monarch, King Faruq, and put Muhammad Naguib as President of the new Republic in his place. An understanding of this period of Egyptian history helps to clarify somewhat the ambivalent attitudes towards the military in Egypt, and the initial expectations of protestors that the military would help protect them from Egypt’s violent security and police services.

Interpretations of Nasserism have centered on the state apparatus. Discussions have focused on the authoritarian-bureaucratic state structure, characterized by a highly state-centralized process of socio-economic development, a corporatist patrimonial state bourgeoisie, a single-party system bolstered by a repressive state apparatus, and a populist nationalist ideology. This political formation, interpreters argue, proved incapable of radically restructuring the Egyptian state, society, and economy, as signaled by the failure to build a fully industrialized, capitalist or socialist, liberal democratic nation-state.3 This is the classic “authoritarian military dictatorship model” we have been reading about in the press. But such a monolithic model fails to adequately capture the complexity of Nasserism. It fails, in other words, to account for both the “alienations and attachments” of Nasserism.4

Nasserism was, in fact, characterized by new modes of governance, expertise, and social knowledge, namely an ideology and practice of social welfare, premised upon the state apparatus as arbiter not only of economic development, but also of social welfare. Such a social welfare model was premised on an ethical covenant between the people and the state, a social contract in which the possibility of revolutionary or democratic political change was exchanged for piecemeal social reform and the amelioration of the conditions of the working classes. It was further based on a view of “the people” (al-sha’ab) as the generative motor of history and as resources of national wealth (the motor of its development, as it were); and an interventionist policy of social planning and engineering. Social welfare, of course, should not be understood as a benevolent process whereby the state shepherds citizens in their own welfare. Rather, it entails the social and political process of reproducing particular social relations, often based on violence and coercion, at least partly to minimize class antagonisms.5

Such a model was predicated on a foundational violence which can be traced back to the Spring of 1954 during which a united front of Wafdists, Communists, Muslim Brothers, and others demanded an end to the military dictatorship and a return to civilian rule and the constitutional system. Demonstrators, led largely by students, flooded the streets in March as they surrounded Abdin palace and demanded political freedoms. After a series of negotiations and political maneuvers, Nasser consolidated his rule, becoming Premier and president of the Revolutionary Command Council in April of 1954.6 Politically, the regime sought to contain the possibility of any broad-based popular movement, hence the attempts at cooptation and the violence perpetrated against its two main ideological contenders, the Muslim Brothers and the Marxist-Communist Left, as well as the abolition of political parties and organizations. Similarly, the regime’s policy towards labor activism and trade unionism was characterized by a two-pronged policy of co-optation of labor and union leaders through their incorporation into the state apparatus and extensive revisions of labor legislation (for example, legislating job security and improved material benefits). Autonomous labor action and the political independence of the trade unions were curtailed by a legislative ban on all strikes, laws on the arbitration and conciliation of labor disputes, and a new trade-union law.7 This provides an important larger context for understanding the historical significance of the newly emerging independent public sector trade unions active in the 2011 protests.

The Nasser regime concentrated its efforts on dismantling the old landed aristocracy through agrarian reform and co-opting the old industrial bourgeoisie to further its own aims of large-scale national industrialization. The new class that emerged and characterized the state public sector, however, was a “state bourgeoisie,” made up of the new class of technocrats together with older elements of the industrial, financial, and commercial bourgeoisie who worked their way into the public sector.8

Nasserism thus represented the formation of a state capitalist class, the liquidation of its main ideological rivals, and the suppression of popular mobilization from below even as it was coupled with a powerful social welfare ideology and a charismatic anti-imperialist rhetoric (immensely strengthened by Egypt’s mobilization in the face of a tri-partite foreign aggression and nationalization of the Suez Canal). This social welfare model can be seen as a Faustian bargain in which “the people” exchanged democratic political liberties and a more radical restructuring of the social order for social welfare programs that deflected attention away from the restructuring of class relations, by emphasizing the piecemeal and palliative reforms for the laboring classes. In other words, it was a passive revolution.

1974 Neo-liberalism

The demise of Nasserism was a complex product of both internal ideological and class contradictions within the regime’s pursuit of socialism, and of external political conflicts, namely, the 1967 war with Israel. The liberalization policies of Egypt’s Infitah (opening) were inaugurated by Anwar Sadat’s Presidential Working Paper of October 1974, in an attempt to create a transition to a free-market economy. Infitah paved the way for a different set of international and domestic relations, characterized by a general rapprochement with foreign capital and a strengthening of the private sector through a series of governmental concessions, that is to say a dual internal and external process of liberalization.

Among the marked features of Infitah, enabled through a series of regulatory interventions as well as a shift in global conditions of capitalism, were the creation of a favorable environment for foreign investment projects (usually in the form of joint ventures), through a new investment law containing various privileges (such as tax exemptions for foreign ventures); a decentralization and liberalization of foreign trade, signaling the end of the public-sector monopoly on foreign trade and the opening up of the economy to foreign goods through the private sector; an expansive influx of international aid; government liberalization of fiscal policy; the abolition of public holding companies previously in charge of planning, coordinating, and supervising the public sector and a concomitant decentralization in state economic planning; and the weakening of the state’s control over public enterprise through a liberalization of wage and employment regulations, facilitated in part by a redefinition of the public sector, thereby leaving private-sector management with more autonomy.9

The predominant agents and architects of Infitah were a combination of members of the old industrial bourgeoisie who had managed to insinuate themselves into the state apparatus after the 1952 revolution; members of the state technocratic bourgeoisie that emerged under Nasser (the upper stratum of the bureaucratic and managerial elite, high-ranking civil servants, army officers and directors, managers of public-sector companies, etc.); and the emerging commercial bourgeoisie whose financial activities were opened up by Infitah—wholesale traders, contractors, importer-exporters, etc.10 This, in part, explains the complexity of the military apparatus divided between the elite echelon of the military (given their involvement in capital accumulation during Infitah) and rank and file soldiers, and the economic gap between them.

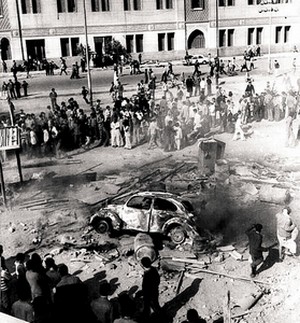

With the IMF-mandated structural adjustment policies of the 1990s, these processes were greatly intensified with the concentration of capital into ever fewer hands. Thus large business oligopolies, such as those of the Sawiris family—local agents of Hewlett Packard and Microsoft, founded Orascom in 1976, a family business that has prospered greatly under Mubarak.11 Naguib Sawiris, one of the individuals put forth for the so-called “Committee of the Wise,” built his fortune, it is worth recalling, at the intersection of government (both civilian and military) contracts and ties with private banks. This is the distinction currently being drawn by many business leaders in Egypt between nationalist and neo-liberal capital, in an effort to bolster their legitimacy. Such an attempt at legitimacy, however, will not be easily digested in a post-Mubarak era by those who have suffered immensely under this neo-liberal regime. With neo-liberalism has come the retreat of the state sector and the elimination of many of the safety net social welfare benefits won by the working classes under Nasser. The immense polarization of wealth, drastically exacerbated since the 1990s, has left many Egyptians consumed by the search for food, shelter and human dignity, with an estimated 40 percent living below or near the poverty line. Crucially, these policies have not gone entirely uncontested as demonstrated by the Bread Riots in 1977 and the Central Security Services (amn markazi) riots in 1986.

2011

Rather than view the spontaneous eruption of protests on January 25, 2011 as signaling the absence of ideological or political cohesion, we can view it instead as the product of an unprecedented historical assemblage of complex forces and contradictions. As Mohammed Bamyeh noted in “The Egyptian Revolution: First Impressions from the Field,” the revolt has been characterized by a large degree of spontaneity, marginality, a call for civic government, and an elevation of political grievances above economic grievances. Thus, we have seen the participation of a wide range of groups with differing ideological orientations but nonetheless coherent and articulate in their demand for an end to the ancien regime. These have included strong elements of trade unions and other labor movements, inspired by the 2006 strike in Mahalla. But labor movements do not exhaust the types of players involved—including, of course, the new social movements (whether leftist, feminist, legal-judicial, NGO based, or social-media galvanized organizations) discussed in Paul Amar’s “Why Mubarak is Out,” as well as the Muslim Brotherhood who have publicly declared their commitment to a civil and pluralist government.

Those on the ground in Egypt know what they want: an end to Mubarak, and end to the emergency laws that have strangled political expression in Egypt since 1981, a civil government with a new constitution guaranteeing elections and the curtailment of political power, and trials for those involved in the massacres of the protesters. Despite the machinations of the West, it is clear that what will simply not do is an insinuation of ancien regime forces of any kind into a post-Mubarak Egypt, whether neo-liberal robber barons, counter-revolutionaries, or political opportunists. The voices from Tahrir, Alexandria, Mahalla, Suez, and Minya must be heard in their call for a “reversal of the relationship of forces.”12 In other words, this is a people’s revolution.

A first version of this text was published by Jadaliyya website on February 06, 2011